High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages were characterized by the urbanization of Europe, military expansion, and intellectual revival that historians identify between the 11th century and the end of the 13th century. This revival was aided by the conversion of the raiding Scandinavians and Hungarians to Christianity, by the assertion of power by Castellans to fill the power vacuum left by the Carolingian decline, and not least by the increased contact with Islamic civilization, which had preserved and elaborated all the classic Greek literature forgotten in Europe after the collapse of The Roman Empire. This was now retranslated into Latin, along with newer works of important advances in science and technology (see 12th-century Renaissance).

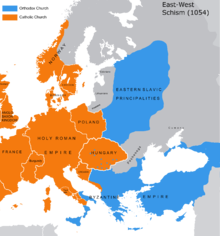

The High Middle Ages saw an explosion in population. This population flowed into towns, sought conquests abroad, or cleared land for cultivation. The cities of antiquity had been clustered around the Mediterranean. By 1200, the growing urban centres were in the centre of the continent, connected by roads or rivers. By the end of this period, Paris might have had as many as 200,000 inhabitants. In central and northern Italy and in Flanders, the rise of towns that were, to some degree, self-governing, stimulated the economy and created an environment for new types of religious and trade associations. Trading cities on the shores of the Baltic entered into agreements known as the Hanseatic League, and Italian city-states such as Venice, Genoa, and Pisa expanded their trade throughout the Mediterranean. This period marks a formative one in the history of the western state as we know it, for kings in France, England, and Spain consolidated their power during this period, setting up lasting institutions to help them govern. Also new kingdoms like Hungary and Poland, after their sedentarization and conversion to Christianity, became Central-European powers. Hungary, especially, became the "Gate to Europe" from Asia, and bastion of Christianity against the invaders from the East until the 16th century and the onslaught by the Ottoman Empire. The Papacy, which had long since created an ideology of independence from the secular kings, first asserted its claims to temporal authority over the entire Christian world. The entity that historians call the Papal Monarchy reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of Innocent III. Northern Crusades and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously pagan regions in the Baltic and Finnic northeast brought the forced assimilation of numerous native peoples to the European identity. With the brief exception of the Kipchak and Mongol invasions, major barbarian incursions ceased.

The High Middle Ages saw an explosion in population. This population flowed into towns, sought conquests abroad, or cleared land for cultivation. The cities of antiquity had been clustered around the Mediterranean. By 1200, the growing urban centres were in the centre of the continent, connected by roads or rivers. By the end of this period, Paris might have had as many as 200,000 inhabitants. In central and northern Italy and in Flanders, the rise of towns that were, to some degree, self-governing, stimulated the economy and created an environment for new types of religious and trade associations. Trading cities on the shores of the Baltic entered into agreements known as the Hanseatic League, and Italian city-states such as Venice, Genoa, and Pisa expanded their trade throughout the Mediterranean. This period marks a formative one in the history of the western state as we know it, for kings in France, England, and Spain consolidated their power during this period, setting up lasting institutions to help them govern. Also new kingdoms like Hungary and Poland, after their sedentarization and conversion to Christianity, became Central-European powers. Hungary, especially, became the "Gate to Europe" from Asia, and bastion of Christianity against the invaders from the East until the 16th century and the onslaught by the Ottoman Empire. The Papacy, which had long since created an ideology of independence from the secular kings, first asserted its claims to temporal authority over the entire Christian world. The entity that historians call the Papal Monarchy reached its apogee in the early 13th century under the pontificate of Innocent III. Northern Crusades and the advance of Christian kingdoms and military orders into previously pagan regions in the Baltic and Finnic northeast brought the forced assimilation of numerous native peoples to the European identity. With the brief exception of the Kipchak and Mongol invasions, major barbarian incursions ceased.

Crusades

The Crusades were holy wars or armed pilgrimages intended to liberate Jerusalem from Muslim control. Jerusalem was part of the Muslim possessions won during a rapid military expansion in the 7th century through the Near East, Northern Africa, and Anatolia (in modern Turkey). The first Crusade was preached by Pope Urban II at the Council of Clermont in 1095 in response to a request from the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos for aid against further advancement. Urban promised indulgence to any Christian who took the Crusader vow and set off for Jerusalem. The resulting fervour that swept through Europe mobilized tens of thousands of people from all levels of society, and resulted in the capture of Jerusalem in 1099, as well as other regions. The movement found its primary support in the Franks; it is by no coincidence that the Arabs referred to Crusaders generically as "Franj". Although they were minorities within this region, the Crusaders tried to consolidate their conquests as a number of Crusader states � the Kingdom of Jerusalem, as well as the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli (collectively Outremer). During the 12th century and 13th century, there were a series of conflicts between these states and surrounding Islamic ones. Crusades were essentially resupply missions for these embattled kingdoms. Military orders such as the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller were formed to play an integral role in this support.

By the end of the Middle Ages, the Christian Crusaders had captured all the Islamic territories in modern Spain, Portugal, and Southern Italy. Meanwhile, Islamic counter-attacks had retaken all the Crusader possessions on the Asian mainland, leaving a de facto boundary between Islam and western Christianity that continued until modern times.

Substantial areas of northern Europe also remained outside Christian influence until the 11th century or later; these areas also became crusading venues during the expansionist High Middle Ages. Throughout this period, the Byzantine Empire was in decline, having peaked in influence during the High Middle Ages. Beginning with the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, the empire underwent a cycle of decline and renewal, including the sacking of Constantinople by the Fourth Crusade in 1204. After that, Andrew II of Hungary assembled the biggest army in the history of the Crusades, and moved his troops as a leading figure in the Fifth Crusade, reaching Cyprus and later Lebanon, coming back home in 1218.

Science and technology

During the early Middle Ages and the Islamic Golden Age, Islamic philosophy, science, and technology were more advanced than in Western Europe. Islamic scholars both preserved and built upon earlier Ancient Greek and Roman traditions and added their own inventions and innovations. Islamic al-Andalus passed much of this on to Europe (see Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe). The replacement of Roman numerals with the decimal positional number system and the invention of algebra allowed more advanced mathematics. Another consequence was that the Latin-speaking world regained access to lost classical literature and philosophy. Latin translations of the 12th century fed a passion for Aristotelian philosophy and Islamic science that is frequently referred to as the Renaissance of the 12th century. Meanwhile, trade grew throughout Europe as the dangers of travel were reduced, and steady economic growth resumed. Cathedral schools and monasteries ceased to be the sole sources of education in the 11th century when universities were established in major European cities. Literacy became available to a wider class of people, and there were major advances in art, sculpture, music, and architecture. Large cathedrals were built across Europe, first in the Romanesque, and later in the more decorative Gothic style.

During the early Middle Ages and the Islamic Golden Age, Islamic philosophy, science, and technology were more advanced than in Western Europe. Islamic scholars both preserved and built upon earlier Ancient Greek and Roman traditions and added their own inventions and innovations. Islamic al-Andalus passed much of this on to Europe (see Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe). The replacement of Roman numerals with the decimal positional number system and the invention of algebra allowed more advanced mathematics. Another consequence was that the Latin-speaking world regained access to lost classical literature and philosophy. Latin translations of the 12th century fed a passion for Aristotelian philosophy and Islamic science that is frequently referred to as the Renaissance of the 12th century. Meanwhile, trade grew throughout Europe as the dangers of travel were reduced, and steady economic growth resumed. Cathedral schools and monasteries ceased to be the sole sources of education in the 11th century when universities were established in major European cities. Literacy became available to a wider class of people, and there were major advances in art, sculpture, music, and architecture. Large cathedrals were built across Europe, first in the Romanesque, and later in the more decorative Gothic style.

During the 12th and 13th century in Europe, there was a radical change in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing traditional means of production, and economic growth. The period saw major technological advances, including the invention of cannon, spectacles, and artesian wells, and the cross-cultural introduction of gunpowder, silk, the compass, and the astrolabe from the east. One major agricultural innovation during this period was the development of a 3-field rotation system for planting crops (as opposed the 2-field system that was being used). Further, the development of the heavy plow allowed for a rise in communal agriculture as most individuals could not afford to do it by themselves. As a result, medieval villages had formed a type of collective ownership and communal agriculture where the use of horses allowed villages to grow.

There were also great improvements to ships and the clock. The latter advances made possible the dawn of the Age of Exploration. At the same time, huge numbers of Greek and Arabic works on medicine and the sciences were translated and distributed throughout Europe. Aristotle especially became very important, his rational and logical approach to knowledge influencing the scholars at the newly forming universities which were absorbing and disseminating the new knowledge during the 12th century Renaissance.

Changes

Monastic reform became an important issue during the 11th century, when elites began to worry that monks were not adhering to their Rules with the discipline that was required for a good religious life. During this time, it was believed that monks were performing a very practical task by sending their prayers to God and inducing Him to make the world a better place for the virtuous. The time invested in this activity would be wasted, however, if the monks were not virtuous. The monastery of Cluny, founded in the Macon in 909, was founded as part of a larger movement of monastic reform in response to this fear.It was a reformed monastery that quickly established a reputation for austerity and rigour. Cluny sought to maintain the high quality of spiritual life by electing its own abbot from within the cloister, and maintained an economic and political independence from local lords by placing itself under the protection of the Pope. Cluny provided a popular solution to the problem of bad monastic codes, and in the 11th century its abbots were frequently called to participate in imperial politics as well as reform monasteries in France and Italy.

The monastic reform inspired change in the secular church, as well. The ideals that it was based upon were brought to the papacy by Pope Leo IX on his election in 1049, providing the ideology of clerical independence that fuelled the Investiture Controversy in the late 11th century. The Investiture Controversy involved Pope Gregory VII and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, who initially clashed over a specific bishop's appointment and turned into a battle over the ideas of investiture, clerical marriage, and simony. The Emperor, as a Christian ruler, saw the protection of the Church as one of his great rights and responsibilities. The Papacy, however, had begun insisting on its independence from secular lords. The open warfare ended with Henry IV's occupation of Rome in 1085 and the death of the Pope several months later, but the issues themselves remained unresolved even after the compromise of 1122 known as the Concordat of Worms. The conflict represents a significant stage in the creation of a papal monarchy separate from and equal to lay authorities. It also had the permanent consequence of empowering German princes at the expense of the German emperors.

The High Middle Ages was a period of great religious movements. The Crusades, which have already been mentioned, have an undeniable religious aspect. Monastic reform was similarly a religious movement effected by monks and elites. Other groups sought to participate in new forms of religious life. Landed elites financed the construction of new parish churches in the European countryside, which increased the Church's impact upon the daily lives of peasants. Cathedral canons adopted monastic rules, groups of peasants and laypeople abandoned their possessions to live like the Apostles, and people formulated ideas about their religion that were deemed heretical. Although the success of the 12th century papacy in fashioning a Church that progressively affected the daily lives of everyday people cannot be denied, there are still indicators that the tail could wag the dog. The new religious groups called the Waldensians and the Humiliati were condemned for their refusal to accept a life of cloistered monasticism. In many aspects, however, they were not very different from the Franciscans and the Dominicans, who were approved by the papacy in the early 13th century (the Franciscan and the Dominican friars developed the popular sermon). The picture that modern historians of the religious life present is one of great religious zeal welling up from the peasantry during the High Middle Ages, with clerical elites striving, only sometimes successfully, to understand and channel this power into familiar paths.