Early Middle Ages

Breakdown of Roman society

The breakdown of Roman society was dramatic. The patchwork of petty rulers was incapable of supporting the depth of civic infrastructure required to maintain libraries, public baths, arenas, and major educational institutions. Any new building was on a far smaller scale than before. The social effects of the fracture of the Roman state were manifold. Cities and merchants lost the economic benefits of safe conditions for trade and manufacture, and intellectual development suffered from the loss of a unified cultural and educational milieu of far-ranging connections.

The breakdown of Roman society was dramatic. The patchwork of petty rulers was incapable of supporting the depth of civic infrastructure required to maintain libraries, public baths, arenas, and major educational institutions. Any new building was on a far smaller scale than before. The social effects of the fracture of the Roman state were manifold. Cities and merchants lost the economic benefits of safe conditions for trade and manufacture, and intellectual development suffered from the loss of a unified cultural and educational milieu of far-ranging connections.

As it became unsafe to travel or carry goods over any distance, there was a collapse in trade and manufacture for export. The major industries that depended on long-distance trade, such as large-scale pottery manufacture, vanished almost overnight in places like Britain. Whereas sites like Tintagel in Cornwall (the extreme southwest of modern day England) had managed to obtain supplies of Mediterranean luxury goods well into the 6th century, this connection was now lost.

Between the 5th and 8th centuries, new peoples and powerful individuals filled the political void left by Roman centralized government. Germanic tribes established regional hegemonies within the former boundaries of the Empire, creating divided, decentralized kingdoms like those of the Ostrogoths in Italy, the Suevi in Gallaecia, the Visigoths in Hispania, the Franks and Burgundians in Gaul and western Germany, the Angles and the Saxons in Britain, and the Vandals in North Africa.

Roman landholders beyond the confines of city walls were also vulnerable to extreme changes, and they could not simply pack up their land and move elsewhere. Some were dispossessed and fled to Byzantine regions; others quickly pledged their allegiances to their new rulers. In areas like Spain and Italy, this often meant little more than acknowledging a new overlord, while Roman forms of law and religion could be maintained. In other areas, where there was a greater weight of population movement, it might be necessary to adopt new modes of dress, language, and custom.

The Muslim conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries of the Persian Empire, Roman Syria, Roman Egypt, Roman North Africa, Visigothic Spain, Sicily and southern Italy eroded the area of the Roman Empire and controlled strategic areas of the Mediterranean. By the end of the 8th century, the former Western Roman Empire was decentralized and overwhelmingly rural.

Church and monasticism

The Catholic Church, which means "universal church", was the major unifying cultural influence. It preserved selections from Latin learning, maintained the art of writing, and provided centralized administration through its network of bishops. Some regions that were populated by Catholics were conquered by Arian rulers, which provoked much tension between Arian kings and the Catholic hierarchy. Clovis I of the Franks is a well-known example of a barbarian king who chose Catholic orthodoxy over Arianism. His conversion marked a turning point for the Frankish tribes of Gaul.

Bishops were central to Middle Age society due to the literacy they possessed. As a result, they often played a significant role in governance. However, beyond the core areas of Western Europe, there remained many peoples with little or no contact with Christianity or with classical Roman culture. Martial societies such as the Avars and the Vikings were still capable of causing major disruption to the newly emerging societies of Western Europe.

The Early Middle Ages witnessed the rise of monasticism within the west. Although the impulse to withdraw from society to focus upon a spiritual life is experienced by people of all cultures, the shape of European monasticism was determined by traditions and ideas that originated in the deserts of Egypt and Syria. The style of monasticism that focuses on community experience of the spiritual life, called cenobitism, was pioneered by the saint Pachomius in the 4th century. Monastic ideals spread from Egypt to western Europe in the 5th and 6th centuries through hagiographical literature such as the Life of Saint Anthony.

Saint Benedict wrote the definitive Rule for western monasticism during the 6th century, detailing the administrative and spiritual responsibilities of a community of monks led by an abbot. The style of monasticism based upon the Benedictine Rule spread widely rapidly across Europe, replacing small clusters of cenobites. Monks and monasteries had a deep effect upon the religious and political life of the Early Middle Ages, in various cases acting as land trusts for powerful families, centres of propaganda and royal support in newly conquered regions, bases for mission, and proselytization. In addition, they were the main and sometimes only outposts of education and literacy in a region.

Carolingians

A nucleus of power unfolded in a region of northern Gaul and developed into kingdoms called Austrasia and Neustria. These kingdoms were ruled for three centuries by a dynasty of kings called the Merovingians, after their mythical founder Merovech. The history of the Merovingian kingdoms is one of family politics that frequently erupted into civil warfare between the branches of the family. The legitimacy of the Merovingian throne was granted by a reverence for the bloodline, and, even after powerful members of the Austrasian court, the mayors of the palace, took de facto power during the 7th century, the Merovingians were kept as ceremonial figureheads. The Merovingians engaged in trade with northern Europe through Baltic trade routes known to historians as the Northern Arc trade, and they are known to have minted small-denomination silver pennies called sceattae for circulation. Aspects of Merovingian culture could be described as "Romanized", such as the high value placed on Roman coinage as a symbol of rulership and the patronage of monasteries and bishoprics. Some have hypothesized that the Merovingians were in contact with Byzantium. The Merovingians also buried the dead of their elite families in grave mounds and traced their lineage to a mythical sea beast called the Quinotaur.

A nucleus of power unfolded in a region of northern Gaul and developed into kingdoms called Austrasia and Neustria. These kingdoms were ruled for three centuries by a dynasty of kings called the Merovingians, after their mythical founder Merovech. The history of the Merovingian kingdoms is one of family politics that frequently erupted into civil warfare between the branches of the family. The legitimacy of the Merovingian throne was granted by a reverence for the bloodline, and, even after powerful members of the Austrasian court, the mayors of the palace, took de facto power during the 7th century, the Merovingians were kept as ceremonial figureheads. The Merovingians engaged in trade with northern Europe through Baltic trade routes known to historians as the Northern Arc trade, and they are known to have minted small-denomination silver pennies called sceattae for circulation. Aspects of Merovingian culture could be described as "Romanized", such as the high value placed on Roman coinage as a symbol of rulership and the patronage of monasteries and bishoprics. Some have hypothesized that the Merovingians were in contact with Byzantium. The Merovingians also buried the dead of their elite families in grave mounds and traced their lineage to a mythical sea beast called the Quinotaur.

The 7th century was a tumultuous period of civil wars between Austrasia and Neustria. Such warfare was exploited by the patriarch of a family line, Pippin of Landen, who curried favour with the Merovingians and had himself installed in the office of Mayor of the Palace at the service of the King. From this position of great influence, Pippin accrued wealth and supporters. Later members of his family line inherited the office, acting as advisors and regents. The dynasty took a new direction in 732, when Charles Martel won the Battle of Tours, halting the advance of Muslim armies across the Pyrenees.

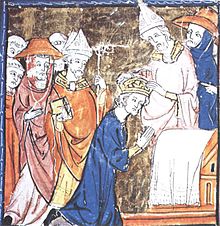

The Carolingian dynasty, as the successors to Charles Martel are known, officially took control of the kingdoms of Austrasia and Neustria in a coup of 753 led by Pippin III. A contemporary chronicle claims that Pippin sought, and gained, authority for this coup from the Pope. Pippin's successful coup was reinforced with propaganda that portrayed the Merovingians as inept or cruel rulers and exalted the accomplishments of Charles Martel and circulated stories of the family's great piety. At the time of his death in 783, Pippin left his kingdoms in the hands of his two sons, Charles and Carloman. When Carloman died of natural causes, Charles blocked the succession of Carloman's minor son and installed himself as the king of the united Austrasia and Neustria. This Charles, known to his contemporaries as Charles the Great or Charlemagne, embarked in 774 upon a program of systematic expansion that would unify a large portion of Europe. In the wars that lasted just beyond 800, he rewarded loyal allies with war booty and command over parcels of land. Much of the nobility of the High Middle Ages was to claim its roots in the Carolingian nobility that was generated during this period of expansion.

The Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne on Christmas Day of 800 is frequently regarded as a turning-point in medieval history, because it filled a power vacancy that had existed since 476. It also marks a change in Charlemagne's leadership, which assumed a more imperial character and tackled difficult aspects of controlling an empire. He established a system of diplomats who possessed imperial authority, the missi, who in theory provided access to imperial justice in the farthest corners of the empire.He also sought to reform the Church in his domains, pushing for uniformity in liturgy and material culture.

Carolingian Renaissance

Charlemagne's court in Aachen was the centre of a cultural revival that is sometimes referred to as the "Carolingian Renaissance". This period witnessed an increase of literacy, developments in the arts, architecture, and jurisprudence, as well as liturgical and scriptural studies. The English monk Alcuin was invited to Aachen, and brought with him the precise classical Latin education that was available in the monasteries of Northumbria. The return of this Latin proficiency to the kingdom of the Franks is regarded as an important step in the development of medieval Latin. Charlemagne's chancery made use of a type of script currently known as Carolingian minuscule, providing a common writing style that allowed for communication across most of Europe. After the decline of the Carolingian dynasty, the rise of the Saxon Dynasty in Germany was accompanied by the Ottonian Renaissance.

Breakup of the Carolingian empire

While Charlemagne continued the Frankish tradition of dividing the regnum (kingdom) between all his heirs (at least those of age), the assumption of the imperium (imperial title) supplied a unifying force not available previously. Charlemagne was succeeded by his only legitimate son of adult age at his death, Louis the Pious.

Louis's long reign of 26 years was marked by numerous divisions of the empire among his sons and, after 829, numerous civil wars between various alliances of father and sons against other sons to determine a just division by battle. The final division was made at Cremieux in 838. The Emperor Louis recognized his eldest son Lothair I as emperor and confirmed him in the Regnum Italicum (Italy). He divided the rest of the empire between Lothair and Charles the Bald, his youngest son, giving Lothair the opportunity to choose his half. He chose East Francia, which comprised the empire on both banks of the Rhine and eastwards, leaving Charles West Francia, which comprised the empire to the west of the Rhineland and the Alps. Louis the German, the middle child, who had been rebellious to the last, was allowed to keep his subregnum of Bavaria under the suzerainty of his elder brother. The division was not undisputed. Pepin II of Aquitaine, the emperor's grandson, rebelled in a contest for Aquitaine, while Louis the German tried to annex all of East Francia. In two final campaigns, the emperor defeated both his rebellious descendants and vindicated the division of Cremieux before dying in 840.

A three-year civil war followed his death. At the end of the conflict, Louis the German was in control of East Francia and Lothair was confined to Italy. By the Treaty of Verdun (843), a kingdom of Middle Francia was created for Lothair in the Low Countries and Burgundy, and his imperial title was recognized. East Francia would eventually morph into the Kingdom of Germany and West Francia into the Kingdom of France, around both of which the history of Western Europe can largely be described as a contest for control of the middle kingdom. Charlemagne's grandsons and great-grandsons divided their kingdoms between their sons until all the various regna and the imperial title fell into the hands of Charles the Fat by 884. He was deposed in 887 and died in 888, to be replaced in all his kingdoms but two (Lotharingia and East Francia) by non-Carolingian "petty kings". The Carolingian Empire was destroyed, though the imperial tradition would eventually lead to the Holy Roman Empire in 962.

The breakup of the Carolingian Empire was accompanied by the invasions, migrations, and raids of external foes as not seen since the Migration Period. The Atlantic and northern shores were harassed by the Vikings, who forced Charles the Bald to issue the Edict of Pistres against them and who besieged Paris in 885�886. The eastern frontiers, especially Germany and Italy, were under constant Magyar assault until their great defeat at the Battle of the Lechfeld in 955. The Saracens also managed to establish bases at Garigliano and Fraxinetum, to sack Rome in 846 and to conquer the islands of Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily, and their pirates raided the Mediterranean coasts, as did the Vikings. The Christianization of the pagan Vikings provided an end to that threat.

Art and architecture

Few large stone buildings were attempted between the Constantinian basilicas of the 4th century, and the 8th century. At this time, the establishment of churches and monasteries, and a comparative political stability, caused the development of a form of stone architecture loosely based upon Roman forms and hence later named Romanesque. Where available, Roman brick and stone buildings were recycled for their materials. From the fairly tentative beginnings known as the First Romanesque, the style flourished and spread across Europe in a remarkably homogeneous form. The features are massive stone walls, openings topped by semi-circular arches, small windows, and, particularly in France, arched stone vaults and arrows.

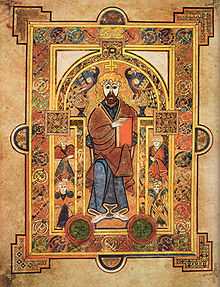

In the decorative arts, Celtic and Germanic barbarian forms were absorbed into Christian art, although the central impulse remained Roman and Byzantine. High quality jewellery and religious imagery were produced throughout Western Europe; Charlemagne and other monarchs provided patronage for religious artworks such as reliquaries and books. Some of the principal artworks of the age were the fabulous Illuminated manuscripts produced by monks on vellum, using gold, silver, and precious pigments to illustrate biblical narratives. Early examples include the Book of Kells and many Carolingian and Ottonian Frankish manuscripts.